Scientists aspire to build nanostructures that mimic the complexity and function of nature’s proteins, but are made of durable and synthetic materials. These microscopic widgets could be customized into incredibly sensitive chemical detectors or long-lasting catalysts, to name a few possible applications.

But as with any craft that requires extreme precision, researchers must first learn how to finesse the materials they’ll use to build these structures. A recent discovery by scientists at the Molecular Foundry who leveraged two of Berkeley Lab’s other user facilities, ALS and NERSC, is a big step in this direction.

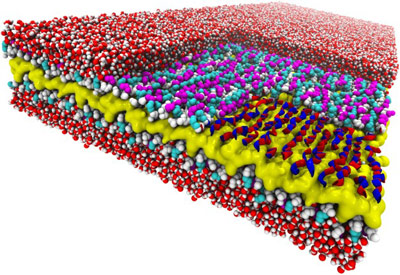

The researchers discovered a design rule that enables a recently created material to exist. The material is a peptoid nanosheet. It’s a flat structure only two molecules thick, and it’s composed of peptoids, which are synthetic polymers closely related to protein-forming peptides.

The design rule controls the way in which polymers adjoin to form the backbones that run the length of nanosheets. Surprisingly, these molecules link together in a counter-rotating pattern not seen in nature. This pattern allows the backbones to remain linear and untwisted, a trait that makes peptoid nanosheets larger and flatter than any biological structure.

The Molecular Foundry scientists say this never-before-seen design rule could be used to piece together complex nanosheet structures and other peptoid assemblies such as nanotubes and crystalline solids.

What’s more, they discovered it by combining computer simulations with x-ray scattering and imaging methods to determine, for the first time, the atomic-resolution structure of peptoid nanosheets.